The Year That Was

San Miguel de Cozumel to San Francisco, California, December 26-31, 2012

Oh, 2012. The Mayans had it right.

I’ve been doing this every year since my early twenties, ritual-compulsive that I am, drafting up a “year in review” with the bombast of all those newsmagazines. Clichés come to mind: best of times/worst of times, new beginnings, trials and tribulations.

Blah blah blah.

But this year, for me and mine, really was a game-changer, and for that reason, I’m taking this bit of introspection and putting it out there for all the world to see.

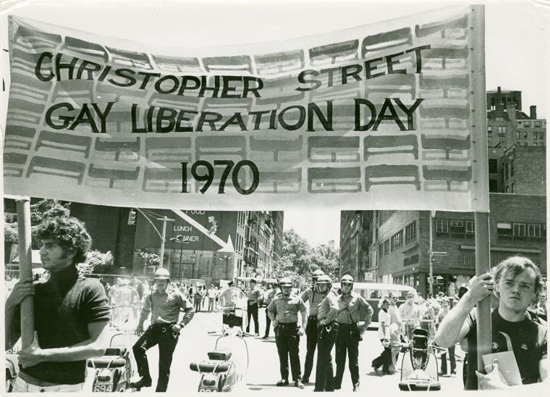

Looking outward, it was actually a pretty good year: the tottering American economy continued to heal from past depredations; the U.S. leadership my crowd favored (hint: begins with a “D” – and with an “O”) won decisive reelection in November; heck, even my home baseball team, the San Francisco Giants, won their second World Series in two years. My career, and that of just about everybody I know, has moved forward smoothly, steadily. One of my sisters is pregnant for the third time, and her family is in the process of moving to an ever-bigger house in Montreal.

My household grew, too: I adopted a cat, vanquishing past fears about pet-owning, and discovering that a seven-pound fluffy feline can (yes!) love and be loved more than in my wildest imaginings.

I even managed to further fatten my already-hefty travel dossier – adding Cairns & Port Douglas, Australia (the Great Barrier Reef: astounding!); Zermatt, Switzerland (snowboarding astride the Matterhorn: amazing!); and Cozumel, Mexico (Mexico! At last, after a decade living in California!) With satisfying work, and with more writing projects and home-improvement projects keeping me busy – as well as greater rapprochement with my liver-donation recipient and ex-partner back east… well, by midyear, 2012 was on track to be one of my best ever. Mantra I kept repeating: please, please, nobody get sick.

Sometimes mantras have the ring of prophecy.

Sometimes, too, years dramatically bifurcate along their midpoint: for me, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2004, 2007, and 2008 were all cleaved in two by life-changing events. And this year?

As 2012 crept on, I began to wonder: shockwaves began occurring close to, though not at, home: a close friend who’d thought she’d left earlier health problems behind saw them flare up, again and again, over the course of the spring, summer, and fall. A former boyfriend, with whom I maintain a friendship (actually I credit him for kicking off the happy precedent of staying on good terms with exes) underwent the ordeal of his father committing suicide one night in April. These were troubles and tragedies, yes, but for me the pattern was familiar: they happened to those near and dear, but no closer.

I rose early on Saturday, July 7, not uncommon for me these days. Soon after, my cell phone rang: my mother. A bit unusual for her to be calling me at 8 a.m. on a Saturday, especially in a quavering voice.

“Your father had a massive heart attack.”

Panic and hope gripped me simultaneously: on the one hand, this was unprecedented for my Dad. His mother had been taken by something similar, but she was ten years older at the time than he presently – and in spite of an ox-like constitution, she’d been chronically sedentary and overweight. My father, though not quite as much the fitness freak as he liked to think, nonetheless enjoyed an active life of skiing, bicycling, tennis, and soccer in his younger years. If anything, the biggest travails of his seventies were significant but treatable complications arising from a series of orthopedic surgeries – a knee replacement, two hip replacements, a bacterial infection.

But one thing about my Dad: his limitless capacity for bounceback. Even though his heart had stopped for forty-some minutes that morning – with my mother performing compressions on him until the ambulance arrived – I was forwarded stories by friends of new procedures (which were performed on him) for cooling and slowly restoring the body’s temperature to prevent damage. Many, many people today suffer cardiac arrest, only to walk out of the hospital a few days later to many more years of life. I was almost expecting that would be the case with my Dad.

Almost.

A few days later the CT scans came back: his brain was irreversibly damaged. The person that he once was – gone, felled by brain-cell necrosis even as heart function was restored. In a whirlwind, I jammed into my suitcase what things I could in the eight minutes it took a taxi to arrive at my home, and high-tailed it to SFO, bound for Montreal and three of the longest days of my life.

Relations between fathers and sons are, I think, always complex. Males in our culture are reared not to be emotionally demonstrative – and though my father was one of the standouts, the sort who cried at every opera… well, his ability to relate affectionately to others was more circumscribed, typical for men of his era. Though we never really fought, he and I, we led lives and embodied personas so distinct it was sometimes hard to believe we were related: he, a product of late-colonial privilege and boarding schools, but too much of a softie to fit in with the hard-nosed business culture of his peers; gifted with languages; a lover of ladies; at once adventurous and dependent, the sort who felt at home doing business in Geneva or Milan, but whose notion of changing a light bulb was “call somebody.”

But then, as I realized after he was gone, more things bind kin than meet the eye. My fixation with fairness came from him. My passion for travel equaled his: in many ways, my big world voyage – and subsequent follow-on journeys – echoed his globetrotting footsteps. I may be gay, but my passion for, well, passion bears more than a passing resemblance to his life of early-1960s ballroom dancing and table-hopping at Miss Montreal.

After the events of the summer, the year took on an altogether different tenor. Further travels were planned with family – including this journey at year’s end; plans and projects continued, albeit at a muted pace. I head into the new year simultaneously at a skip and a shuffle. Fittingly, for a year that saw the passing of a man who so loved nature and the sea, I began 2012 with a dunk in the South Pacific waters off eastern Australia – and ended it with a similar swim in the Caribbean on the far shores of Cozumel, Mexico. Death is a part of life, goes the cliché, and while I’d always been able to be moved by that, knowing it was something of an abstraction, this year the abstract was hardened, crystallized. It’ll be hard to look at a sunset or ocean again without a tinge of sadness.

But then, another cliché: life goes on. With work, with pets, with kitchen remodels, with new family members still in the womb. My father, ever the active sort, would certainly have approved.

Happy New Year 2013.