(with apologies to The Association)

(with apologies to The Association)

Just about four years ago, I moved away from Chicago, my home for almost half a decade (I blogged about that, too, and I’m republishing that post below for those of you without Flash-enabled devices to view my old blog). It was a bittersweet, almost painful goodbye: it meant leaving a long-term partner, a condo I’d remodeled in a charming vintage brick courtyard building in East Lake View, and a pleasant mix of acquaintances and friends.

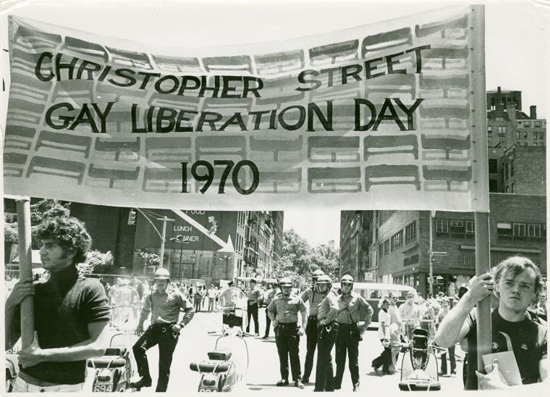

So why on Earth did I leave? As I wrote back then, Chicago was a tough place for an unconventional gay techie nerd like myself. I’d suffered a disastrous run of employment there, and California’s startups and workplace culture — where I’d worked years before — beckoned. So too did a number of old friends who’d weathered the dot-com downturn of the early 2000s and seemed to be flourishing Out West. With the Village People’s exhortation to Go West ringing in my ears, I sailed off into the western sky to re-ignite a life in the City by the Bay.

The results have been decidedly mixed: the career stuff did prove as wonderful as I’d hoped; I also managed to navigate the pricey shoals of San Francisco’s real estate market (okay, the real-estate downturn in 2008-9 helped me out there a bit), and found a place to live that makes me as happy as my Chicago spot once did.

The results have been decidedly mixed: the career stuff did prove as wonderful as I’d hoped; I also managed to navigate the pricey shoals of San Francisco’s real estate market (okay, the real-estate downturn in 2008-9 helped me out there a bit), and found a place to live that makes me as happy as my Chicago spot once did.

But the softer stuff proved, well, softer: I’ve found San Francisco to be a challenging place to put down roots, make friends, find romance and all that goes with it. Some of that may simply be the whims of chance, but I can’t help wondering if a city buffeted by the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and the unstoppable tech juggernaut in the years following can really lay claim to being the communitarian, laid-back bohemian capital it was in decades past. I’ve often said that newly-minted North American boomtowns try to clone those aspects of New York they think befit a “world city”: high prices, materialism, pretension — while often overlooking the eight million other stories in America’s naked city. Consequently, as I boarded my flight to Chicago this past Thursday, I was most curious to see if my fond memories of Midwestern friendliness (outside of the workplace, at least) were simply nostalgic reverie or if I could rekindle that old-time magic once more.

Initial signs were hopeful: I was staying with a friend who’d recently snagged a place in a high-rise in Edgewater, an appropriately-named lakefront district with sweeping views of cobalt-blue Lake Michigan and its beaches. When I first moved to Chicago locals would tell me “it’s like living in a seafront city,” and I didn’t believe them. That is, until I witnessed for myself the shores of the great inland waterway and the amazing work the city’s done to maintain and preserve its waterfront. It rivals — in the summer at least — some of the grandest waterfront cities I’ve lived in or visited — from the beach cities of Los Angeles to Cape Town, South Africa and Sydney, Australia.

I meandered the city’s downtown on Friday, enjoying the warm (but not too warm) weather that I sometimes miss during San Francisco’s “coldest winter I ever spent” (in Twain parlance) of July and August. It was just as I’d remembered: Michigan Avenue, Wacker Drive, and the Loop remain one of the world’s truly grand urban cores, and here too Chicago’s done wonders keeping the place (relatively) safe and clean. The Chicago River is cleaner than it’s ever been since large-scale settlement began here at the confluence of this waterway and the lake beyond (a recently-erected statue to Jean Baptiste Point du Sable bears witness to this history); a riverwalk allows access in a manner remniscient of Paris’s Seine. The Trump building, still a construction site when I left, is now complete and is the city’s fourth-tallest skyscraper — bigger than anything on my side of the Mississippi.

I meandered the city’s downtown on Friday, enjoying the warm (but not too warm) weather that I sometimes miss during San Francisco’s “coldest winter I ever spent” (in Twain parlance) of July and August. It was just as I’d remembered: Michigan Avenue, Wacker Drive, and the Loop remain one of the world’s truly grand urban cores, and here too Chicago’s done wonders keeping the place (relatively) safe and clean. The Chicago River is cleaner than it’s ever been since large-scale settlement began here at the confluence of this waterway and the lake beyond (a recently-erected statue to Jean Baptiste Point du Sable bears witness to this history); a riverwalk allows access in a manner remniscient of Paris’s Seine. The Trump building, still a construction site when I left, is now complete and is the city’s fourth-tallest skyscraper — bigger than anything on my side of the Mississippi.

But beyond the big buildings, it’s the city’s warmth that captivates. After a pleasant rendezvous with my ex and his parents (who used to live in the ‘burbs but relocated to the city a year or so after I left), a bunch of us headed out to the bars of Boystown. A number were unchanged; some had augmented their offerings; others were utterly new. And yes, the friendliness and strong drinks were on tap that night (one wonders how much the latter influences the former). I reconnected with old friends and (yes) made a couple of new ones.

But beyond the big buildings, it’s the city’s warmth that captivates. After a pleasant rendezvous with my ex and his parents (who used to live in the ‘burbs but relocated to the city a year or so after I left), a bunch of us headed out to the bars of Boystown. A number were unchanged; some had augmented their offerings; others were utterly new. And yes, the friendliness and strong drinks were on tap that night (one wonders how much the latter influences the former). I reconnected with old friends and (yes) made a couple of new ones.

Dodging the rain on Saturday, we headed down to the area’s big attraction this past weekend, a two-day street festival, Northalsted Market Days. As chance would have it, I ran into nearly everyone I’d recontacted but hadn’t made concrete plans to see. Later that evening we went for a fabulous (and affordable) meal then hit the town for one more night.

But it was Sunday when things really shone. The rain has swept away the lingering heat and humidity, and the afternoon turned into one of those spectacular days you usually only see in Southern California. A group of us headed north to Ravinia, Chicago’s long-time eclectic outdoor summer music festival, to hear fellow gay Montrealer Rufus Wainwright perform Shakespearean sonnets set to musical accompaniment care of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Afterward, we rendezvous-ed on the balcony of another of my old-time chums for a late-evening drink and afterparty — hanging out on people’s expansive porches is a Chicago tradition, one I’d almost forgotten how much I’d missed.

But it was Sunday when things really shone. The rain has swept away the lingering heat and humidity, and the afternoon turned into one of those spectacular days you usually only see in Southern California. A group of us headed north to Ravinia, Chicago’s long-time eclectic outdoor summer music festival, to hear fellow gay Montrealer Rufus Wainwright perform Shakespearean sonnets set to musical accompaniment care of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Afterward, we rendezvous-ed on the balcony of another of my old-time chums for a late-evening drink and afterparty — hanging out on people’s expansive porches is a Chicago tradition, one I’d almost forgotten how much I’d missed.

Watching dawn break over the lake through the picture windows of my friend’s condo, I pondered the ambiguity of life’s choices: while I don’t regret having pulled up stakes and moved out West, I sometimes feel I left my heart not in San Francisco but here, in this glorious, affable, brawny city by the azure waters in mid-continent. I’ve been away from this place too long, and I have no doubt I’ll be back again soon and often.

Watching dawn break over the lake through the picture windows of my friend’s condo, I pondered the ambiguity of life’s choices: while I don’t regret having pulled up stakes and moved out West, I sometimes feel I left my heart not in San Francisco but here, in this glorious, affable, brawny city by the azure waters in mid-continent. I’ve been away from this place too long, and I have no doubt I’ll be back again soon and often.

—————————————————————-

The (Real) U.S. Capital

Reflections on Chicago as America

(Tue Jun 5 2007)

Mention the words “nation’s capital” in the U.S. and the image that comes to mind is that grandiose yet low-slung southern town on the Potomac, Washington D.C. And yet, as has also been said about New York, Washington D.C. ain’t America.

Although no one place can purport to be the “real” heart of a continent-sized country of 300 million, one gets the sense that the coasts, in all their glory, with all their teeming population centers, represent an America that is, for lack of a better term, somehow un-American. Or so U.S. conservatives would have us believe, with all their railing against the “godless coasts,” replete as they are with mammon, sin, and foreign influence.

If so, where does the “real” America lie? The geographically obvious choice is Kansas — and some recent books, such as Thomas Frank’s What’s The Matter With Kansas, suggest as much. In ages past, prairie populism came roaring out of midcountry to take on the moneyed interests in New York and fight for the little guy. However, this Guilded-Age rhetoric (as Frank’s book points out) has been repackaged as part of a conservative, pro-business ideology that is not uniquely Midwestern. Moreover, while I’m inclined to accept that populism and a certain degree of insularity are part of the American psyche, I’m not sure that Pat Buchanan conservatism is necessarily representative of all (or even most) of the U.S. No, the coastal cities count too, as do the pockets of colorful, progressive, iconoclastic smaller places like Austin, Texas or Madison, Wisconsin. By that token, right-leaning Kansas ain’t really America either. Is there somewhere in this land that encapsulates all of this?

The state that’s often been touted as “America in microcosm” is Missouri, whose landscapes run the gamut from gritty urban industrial centers (with their inner-city ghettos), wealthy suburbs, agrarian hinterlands… even wineries. Having visited there a couple of times, I’m inclined to agree — and next year’s Presidential race will prove interesting as Missouri is usually a bellwether for how the rest of the nation votes.

However, being a city boy, I’m equally interested in finding a city that represents America best, one that would encapsulate much, if not all, of what this country’s about. I think I’ve found it. Having lived here for 4 years (and on the verge of leaving it — the sale of my condo in the city’s Lake View district closes next week), I’m nominating Chicago as best urban candidate to be America In Miniature.

I can’t profess to be an expert, of course, having only come to this country as an adult. But being a bit of an outsider sometimes gives one a perspective that born-and-bred locals lack — witness artist David Hockney’s visions of Los Angeles. In my travels (American cities I’ve visited or lived in include Boston, New York, Washington D.C., Atlanta, Miami, Chicago, St. Louis, Milwaukee, Denver, Salt Lake City, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego), Chicago feels to me most like the America portrayed in art, in song, in film — all rolled together in one skyscraper-sized bundle.

In fact, skyscrapers are a good place to start: Although New York’s edifices are sometimes better known (including, tragically, the Twin Towers of 9/11), Chicago’s behemoths (The Sears Tower, The John Hancock Center, and others) stand toe-to-toe with anything in Gotham; although eclipsed by some new projects in Asia, Chicago’s tallest buildings are still among the biggest around. In fact, this most American of building forms started in the Windy City: The Monadnock and Reliance Buildings in Chicago’s Loop represent some of the first experiments in steel-frame construction, eliminating the need for load-bearing outer walls. This freed architects from the tyranny of gravity (even the biggest of Europe’s medieval cathedrals are only about 15 or so stories high), and let buildings soar skyward. And it began mostly in Chicago during America’s rise to industrial prominence in the later-19th century.

Equally significant, no discussion of Chicago can exclude its food: The place has some of the best around, and even its hometown staples bespeak all-American-ness (steak, deep-dish pizza — for the best of the latter, I recommend ordering from here), with all the caloric excess that implies.

Beyond architecture and gastronomy, Chicago reveals its all-American colors through its people. In one way, they embody what I like best about America — that open, gregarious friendliness so often parodied in movies and the media (“hey, how ya doin’?”). There are few cities where the trendiest restaurants and nightclubs feature small-town-style cheeriness from bouncers and maitres-d. The down-home feel is no accident: Many of Chicago’s residents are transplants (as is true of most big cities), but in Chicago’s case, drawn largely from smaller centers in the nation’s heartland; in spite of its size (it’s a larger metro area than D.C., Boston or the San Francisco Bay Area), it is more a regional center than a national one.

It was that reality that ultimately did in the city’s future as my hometown: As befits a regional center (I imagine Curitiba, Brazil or Chengdu, China suffer the same plight), I found it to be a more conventional-minded place than crazy California or edgy New York. Oh, Chicago does have its art scene (not to mention a terrific theatre community), but it seemed to me that any time “important” work was being done or careers were being made, it was all too often in the context of a large, staid company (in spite of having lost some corporate head offices, the city and surrounding suburbs are still home to Kraft, United Airlines, Accenture, and a host of others); the very-friendly younger set love their liquor but often look with Nancy Reagan-esque disapproval at even the most infrequent use of other substances (a second Amsterdam Chicago will never be). And overall friendliness notwithstanding, there remains an undercurrent of midcountry resentment toward the better-known coasts: One middle manager at a major investment banking firm downtown tried to convince me that the coasts were “silly” (his words) and produce little that folks like him care about; instead, the Midwest, he claimed, was where the best and brightest really lay.

I suppose if there’s one constant I’ve found among all the places I have lived it is provincialism, and sadly there too Chicago does not disappoint.

As I bid adieu to John Hughes country (more evidence of the city’s representative stature — its use as a backdrop in teen flicks of the 1980s), it is with a measure of sadness: It’s a great city, frequently overlooked by foreigners and coastal residents alike. Unfortunately, this reality also means that Chicago misses out on some of what makes the coasts great: The iconoclastic nature of a California high-tech startup; the interplay with academia that is Boston (Chicago has terrific universities as well, but in typical Midwestern fashion the most prestigious schools — Northwestern and The University of Chicago — are some distance from the city, or, in the case of the top state school, in a small town some 200 miles away). Even at its most liberal, at its most progressive, there’s a feeling that the landmass of America insulates Chicago from some of the most colorful and progressive (though, admittedly, not always the best) influences. For a guy like me, who’s always thrived on swimming against the stream… well, somehow the shores of Lake Michigan just didn’t quite fit.

But I will miss the pizza.

I took Daenerys home that afternoon, bracing for the worst: refusal to come out of the “safe room” I’d created for her in my spare bathroom; hiding under bed and sofa; scratching up furniture. Instead, it seemed to me, a miracle occurred: she adjusted to the full expanse of my two-stories and 800 square feet in an afternoon; willingly ate everything that was put in front of her; and slept in my bed that night and every night thereafter.

I took Daenerys home that afternoon, bracing for the worst: refusal to come out of the “safe room” I’d created for her in my spare bathroom; hiding under bed and sofa; scratching up furniture. Instead, it seemed to me, a miracle occurred: she adjusted to the full expanse of my two-stories and 800 square feet in an afternoon; willingly ate everything that was put in front of her; and slept in my bed that night and every night thereafter.